Anxiety, for some, is a word that creates feelings of dread, butterflies and an increased heart rate. It is a word that so many more people are now familiar with.

The media – be it social media, news networks or newspapers and tabloids – often portray anxiety as the jittering sibling of depression. They also suggest it to be one of the main mental health conditions experienced by individuals.

Anxiety can be defined as a “multiple mental and physiological phenomena, including a person’s conscious state of worry over a future unwanted event, or fear of an actual situation. Anxiety and fear are closely related.” ((Foa et al, 2017, p.189 1))

It is an umbrella term given to various subtypes of anxiety. Some commonly diagnosed anxiety disorders include:

- Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD)

- Social anxiety disorder

- Panic disorder

- Phobias

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD)

- Perinatal anxiety or perinatal OCD

For more information on any of the above disorders please visit https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/anxiety-and-panic-attacks/anxiety-disorders/.

What we know:

In any given week in England alone, 6 in 100 people will experience GAD, 4 in 100 will experience PTSD, 2 in 100 will have a phobia, 1 in 100 will experience OCD. This is only what gets reported. It is likely higher (McManus, 20162). There isn’t one cause of anxiety disorders. There are, in fact, many things which could contribute to someone developing anxiety. Genetics, life experiences, drugs (even alcohol and caffeine) and our ever-changing circumstances – to name just a few. We can go through states of feeling anxious daily, form moment to moment. However, anxiety can become a mental health problem if it impacts your ability to live your life as fully as you want to.

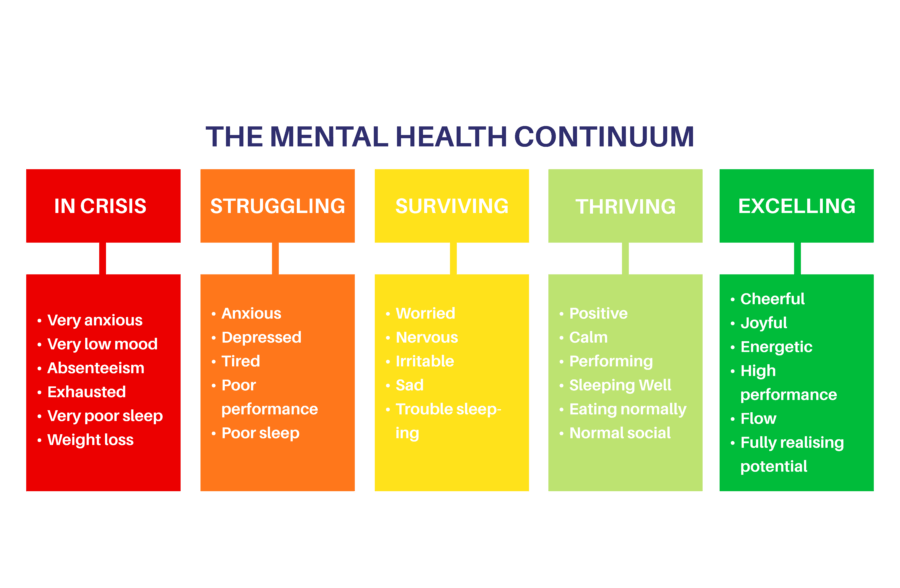

Our mental health and wellbeing is something that is very fluid and dynamic, it changes all the time. So, someone who may have a diagnosis of GAD, may not always experience it, it may come and go, dependant on aspects of our life. Gordon Allport (19373) mentioned in his studies that mental health and illness are not two independent constructs. They are two poles of a linear continuum and keep changing throughout the lifespan. This can be seen as the starting phase to developing what is now referred to as the Mental Health Continuum.

Depending on which variation of the continuum is considered, there are several distinct markers:

- The healthy point

- The problem point

- The disorder point

Some may argue that this use of language does not promote positivity and simplifies the complexity of psychology. Skipping forward a few years and we now have additional language, such as languishing and flourishing.

Within this perspective, mental health disorder or an overall distressed state is referred to as ‘languishing.’ A more positive and content state is called ‘flourishing’.

Similar continuums use words such as ‘struggling’ and ‘thriving’ to describe such states. ‘Surviving’ is a term used to label a middle ground. It is important to remember that we are all capable of moving from one end of the continuum to the other. Being in a red zone does not imply that we cannot be in the green zone again, and vice versa. Being Mentally ill does not mean there is a complete absence of mental health. It just suggests that the person, at that particular point, is experiencing the negative end of their continuum (Chowdhury, 20214).

In truth, we all have moments of anxiety, we can all find ourselves on the not so nice end of the continuum.

From an evolutionary perspective, signs and symptoms of anxiety, our emotions and our physiological reactions, help keep us out of danger, away from predators. They protect what is important to us for survival. Now, our modern world doesn’t seem to have much of a place for those feelings. They can still happen. Our primitive fears no longer play an important role within our lives, but they are still an important part of them.

It is always great to have good tools to allow us to cope with anxiety.

Considering the wellbeing continuum, we can never fully overcome anxiety, it will always be there in some form or another and it can return. How we learn to cope with it and how we view it, those are the important steps. It may be beneficial for some to view anxiety as something that lives with us rather than takes over our lives.

What can you do to cope with anxiety?

Question your thought pattern

Negative thoughts can take over the mind and distort the severity of a situation. So, challenge your fears. Ask if they’re true and if they are based on emotions and feelings. See where you can take back control. Write down your thoughts. Writing down the things that are making you anxious takes it out of your head and can make it less daunting.

Identify and learn to manage your triggers

Identify triggers either on your own or with the help of a therapist. Sometimes they can be obvious, like caffeine, drinking alcohol, or smoking. Other times they can be less obvious and much more situation specific. Long-term problems, such as financial or work-related stressors, may take some time to figure out and problem solve. This may require extra support, through therapy, friends or specific services.

Exposure and response prevention (ERP)

This is used for a range of anxiety disorders, but is particularly effective for helping with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). ERP therapy encourages you to face your fears and let obsessive thoughts occur without ‘putting them right’ or ‘neutralising’ them with compulsions. Exposure therapy starts with confronting items and situations that cause anxiety, but anxiety that you feel able to tolerate. After the first few times, you will find your anxiety does not climb as high and does not last as long. Gradually, progression can be made as you are exposed to more difficult situations.

Adopt cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

CBT helps people learn different ways of thinking about and reacting to anxiety-inducing situations. A therapist can help you develop ways to change negative thought patterns and behaviours before they turn into that downward spiral.

Commit to something that you find calming and relaxing

Focussed deep breathing, meditation, going for a walk, yoga, different forms of mindfulness. Whatever it may be, identify what works for you and set time aside to work it into your week. Aim to make it a daily habit.

Ask your doctor about medication

If your doctor or mental health practitioner believes your anxiety is severe enough, then it may be beneficial to discuss the use of medication. There are a number of options, depending on your symptoms and how your body could react.

In addition to the tips mentioned above, eating healthily, staying active, having a great routine, prioritising sleep and keeping a journal or diary are all things that can be done to be proactive when it comes to managing your mental health.

To-Health’s new ‘Positive Psychology’ workshop looks at a mental health Continuum in more detail, along with talking through a particular model of wellbeing towards achieving positive psychology. It is now available to book so get in touch for more information.

Further Resources

If you require additional information on the topic of anxiety and would like some support, please take a look at the anxiety UK website: https://www.anxietyuk.org.uk/get-involved/research-area/. Alternatively, you can visit the Mental Health UK website for helpful information around anxiety and many other mental health conditions: https://mentalhealth-uk.org/help-and-information/conditions/anxiety-disorders/treatment/

- Foa E. B, Franklin M, McLean C, McNally R. J, Pine D, Costello E. J, Kagan J, Kendall P, Klein R, Leonard H, Liebowitz M, March J, Ollendick T, Pynoos R, Silverman W, Spear L (2017). Treating and Preventing Adolescent Mental Health Disorders: What we know and what we don’t know (2 ed.). Oxford University Press.

- McManus, S, Bebbington P, Jenkins R, Brugha T. (eds.) (2016). Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult psychiatric morbidity survey 2014.

- Allport, G. W. (1937). Personality: A psychological interpretation. New York, NY: Holt.

- Chowdhury, M.R. (May, 2021). What is the mental health continuum model? PositivePsychology.com. https://positivepsychology.com/mental-health-continuum-model/